The sequence flow of the parent process ends in both cases at the left edge of the subprocess. This is, however, the less important option. That means process segments remain localized, and you can attach events too. Yes, it can be helpful to have your subprocess modeled and expandable directly from the parent process. In other words, it supports the first option above. The most important thing is that your tool provides for linking and that you can usefully navigate through the diagrams. This can result in sluggish performance with a complex diagram, and it can be visually nasty. Expanding the subprocess requires that all the adjacent symbols in the diagram shift to make room.

PARALLEL SYMBOL PLUS

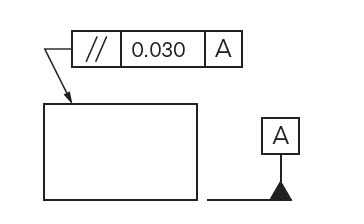

The only difference is the plus sign, indicating a stored detailed sequence for the subprocess:ĭirect expansion may seem appealing, but often it is not useful in practice. Both tasks and subprocesses are part of the activities class and are therefore represented as rectangles with rounded corners. A subprocess describes a detailed sequence, but it takes no more space in the diagram of the parent process than does a task.

PARALLEL SYMBOL SOFTWARE

The possible top-down refinements or bottom-up aggregations mark the difference between true process models and banal flow charts, between sophisticated BPM software products and mere drawing programs.īPMN provides us with the subprocess to help with the expanding/collapsing view. Then you have to develop a detailed description, so that you can analyze exactly where the weak points are or how you’ll have to execute the process in practice.

You have to rough out your processes so that you can get the general ideas in place and recognize correlations. When modeling your process landscape, you don’t have this luxury. The examples in this tutorial either deal with simple processes, or they diagram complex processes superficially so that the models fit on one page. One thing to remember is that if you strive to harmonize your functional and technical process models to achieve a better alignment of business and IT, you inevitably face this type of process modeling whether you use BPMN or not. We will show the usefulness of this new thinking by example. In the medium and long terms, however, avoiding pools denies you a powerful device for increasing the significance of process models. That’s traditional, and it’s a pragmatic solution during, say, a transitional period that allows your co-workers to adapt. You can eliminate pools and work just with lanes, modeling the message exchange as normal tasks as shown before. What does that signify, however, for purely functional process modeling, in which you also describe processes not controlled by such a process engine? There’s no general answer to that question. Have you heard of service orchestration in connection with Service Oriented Architecture (SOA)? That’s almost exactly the task of a process engine, except that these services are not only fully automated web services they also can be tasks executed by human process participants as directed by the process engine. So the process engine equates to the mysterious, almighty process conductor. In that world, the process engine controls all tasks in the process, even though different task managers may execute them. Even though BPMN lanes look very much like those of other process notations, they represent an entirely different way of thinking, which we attribute to BPMN’s origin in the world of process automation. It reveals a basic principle, however, that you must understand. That seems complicated – and you don’t have to choose this method for practical modeling.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)